I. Madness

Many years before you or I were born, during the late Middle Ages and throughout the Renaissance in Europe, people danced. Sometimes it was a sole soul doing the boogie-woogie, sometimes it was thousands upon thousands all writhing and convulsing together. Although I tend to avoid the clurb, I can get down, so normally I’d find any story of dancing to be a happy thing, and it certainly would be in this case if not for the fact that these revelers seemed to have no control over themselves, and could not stop dancing, being as they were: in the throes of madness.

Outbreaks of 'dancing mania' were well-documented in Europe over a period of hundreds of years, where people of all ages were found dancing erratically for days, accompanied only by music in their own minds, often stopping only after collapsing from exhaustion. Although scholars and historians don't agree on the cause of the dancing mania, one likely explanation is that it was a form of mass psychogenic illness, better known as mass hysteria.

Defined as any group experiencing some sort of 'collective nervous system disturbance' with no understood underlying biological cause, reports of mass psychogenic illness are widespread throughout history, often found in high-stress environments, perhaps (and I'm spitballing here) as some sort of unconscious desire to escape from them. In Renaissance Europe, there were countless outbreaks among young women and girls in strict religious convents. They were often thought to be possessed by demons; some were found using blasphemous language and exposing themselves, others were found collectively bleating like sheeps, yelping like dogs, or meowing like cats. In the 18th century there were outbreaks of convulsions among schoolchildren in Germany, Switzerland, and France. In the 20th century, there was laughing in Tanzania, shaking and jerking in upstate NY, feinting and 'overbreathing' in England, and many more.

What is exceptionally fascinating about episodes of mass psychogenic illness and its resulting symptoms is how different the symptoms are. From dancing to yelping to laughing to convulsing to cursing. The symptoms change throughout the millennia. Why?

II. Framing

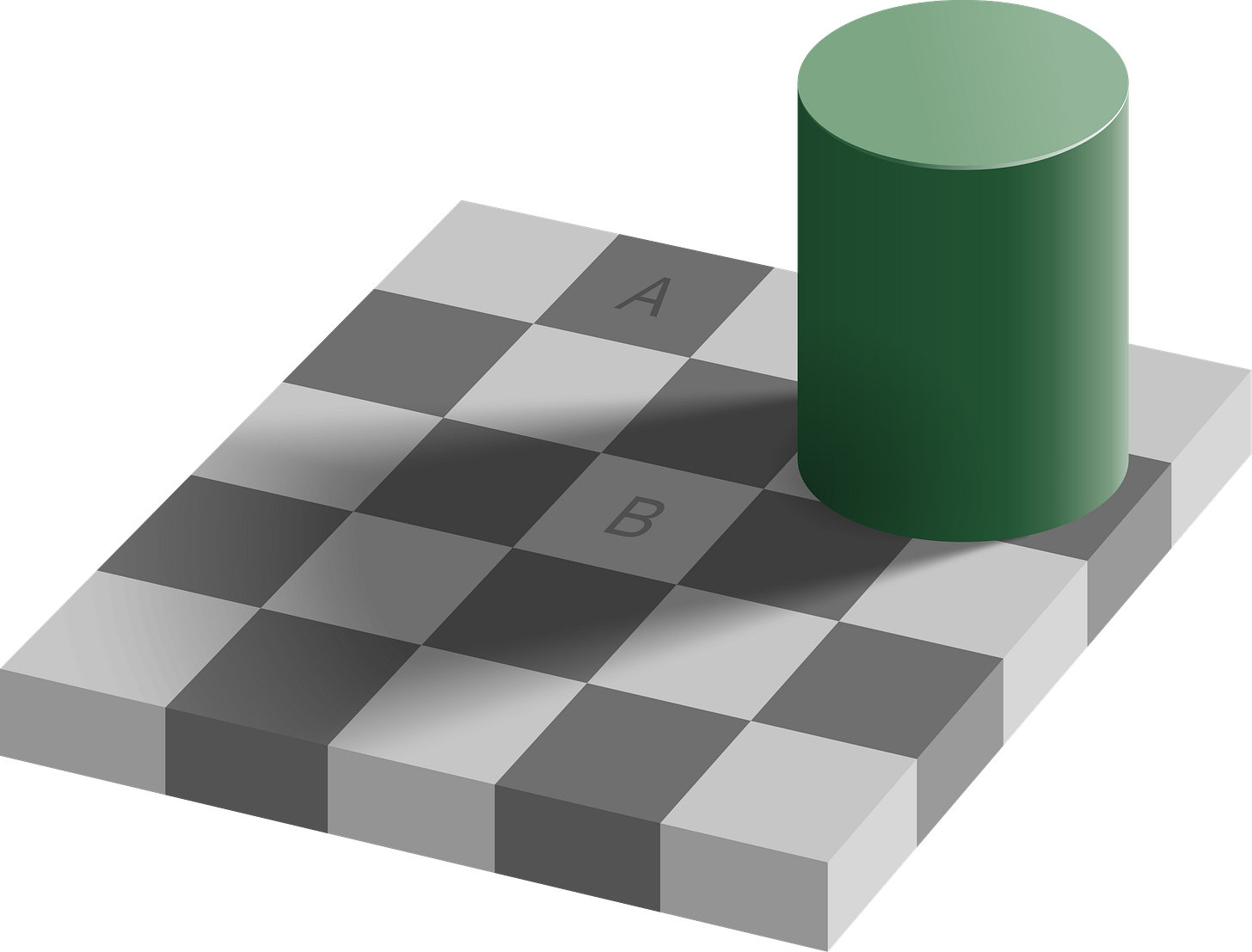

It is a fundamental principle of our perceptual systems that what we see is determined by the context in which we see it. When we look at the checker shadow illusion, we see two squares as being different shades of grey depending on their context.

Consider also gold/blue dress controversy. But it’s not just vision, see (ahem, listen to): the Yanny vs Laurel debate or, for an even more mind-bending one, considering the syllable difference, listen to Brainstorm vs Green Needle.

Perception, and therefore meaning, is determined by framing. Consider the matte of a framed photograph, the size of a plate carrying a tiny and delicate 5-star nibble, the placement of a punchline in a joke, or the timing of the reveal in a magic trick.

Change the frame, change the experience. Reading a book recommended by someone you aspire to be like will resonate very differently than when that same book is recommended by a social villain. Same with a song, a joke, a play, advice, or anything.

Framing is also the foundation of the psychology of choice. Tversky and Kahneman, 1981 found that a question framed in two different ways can result in two different answers. Related to this is the idea at the heart of the book Nudge, written by Nobel Prize winning economist Richard Thaler and equally impressive Cass Sunstein, of ‘Libertarian Paternalism,’ the act of designing contexts in which people can more easily make the decisions they want to make. (e.g. Google HQ has free candy, but it’s placed in opaque containers, on the lowest shelf; if you have to put more effort to get at the candy than the apple, more often you won’t reach for it.) Framing ultimately comes down to attention, see: the basketball awareness test.

Understanding that we act differently based on the context in which we decide is hugely important for how we design our world, from deleting social media to living near your gym to how your couches are set up in your house (in front of your TV, or facing each other?).

III. Agency

In high school, I experimented with a unique drug: hypnosis. Being close to clinically obsessed with magic and mentalism and psychology, it was a natural evolution; “You can hypnotize people do do things?!” I found hypnosis ‘scripts’ online and in books, printed or copied them out, and spent my lunchtimes in an empty band room making my friends *snap!* “SLEEP! All the way down, all the way deep, all the way sound asleep just drifting and floating with the sound of my voice at the center of your head…” Word got out, and after a few weeks there were small crowds watching impromptu hypnosis shows accompanied by the occasional symbol crash or trumpet blast.

Although I don’t do hypnosis anymore, I still find the experiences I had as a youth with it, and reports of it in others, and research in clinical hypnotherapy, and Derren Brown, captivating. Hypnosis seems to allow people, as in the throes of madness, religious ecstasy, or political rallies, to forgo critical thinking and offload agency to another entity, fully and completely. Although in hypnosis, the difference is that it is (mostly) voluntary, and calm, and often pleasant (unless Derren Brown steals your wallet).

One of the most fascinating and paradoxical things about hypnosis is that for the most part, it only works if the subject thinks it works. There is an entanglement with the power of authority here. Having considered becoming a clinical psychologist and being someone with an appreciation of the dramatic, I was at first blown away and then increasingly disturbed by Tony Robins: I Am Not Your Guru, a documentary that shows highlights from Tony Robbins seminars. Watch and you will see people having peak experiences of breakthrough through breakdown, and finding Acceptance equal only to that found inside MDMA trips and foxholes. What is curious is that I find myself in part believing that some people may need to offload agency to a tough-love authority to change, and knowing that some people certainly do not.

The power of the cult leader, the visionary, and the storyteller are often one and the same; the power of Mesmer: they have convinced us that they have it.

IV. Conclusion

Dissociation and hyper-suggestibility seem to increase as a result of stress or confusion, resulting in increased likelihood of offloading of personal agency to authority or groupthink. Consider the last time you were highly stressed. In high-stress situations, most would agree much more readily to do just about anything to get out of that feeling. And the higher the stress, the more we desire an escape rope. Cults and “leadership seminars” often attract anxious, lost people looking for confident answers like moths to a flame. Derren Brown uses confusion and social pressure to coerce suggestible people into acting strangely. The stress of the experiences of being trapped in a convent, boarding school, or refugee camp might lead any sane person to try to find an out, even if that out is losing one’s mind and dancing oneself into exhaustion or meowing. And that we often look to each other to see how to act should be no surprise.

The context of context, the framing of madness, and the illusion of agency demonstrate different parts of a deeply held delusion. We all disassociate and forgo agency. Bleating nuns, leadership seminars, hypno-mind-hacking may seem like extreme examples, but there’s no reason to think that micro psychogenic illness doesn’t exist in small ways, every day, in all of us. From our opinions on art and culture, books and TV, politics and relationships, in more ways than we recognize, we are a product of our environments, continually looking out, creating expectations upon expectations upon expectations upon which we build our models of reality.

Thanks for reading this week’s Delusion. Please consider subscribing if you’re not, or sharing with a friend. Agree? Disagree? Please leave a comment below.